The following is a guest post by Luzzie Normand:

We have all been there. You are sitting at work gazing at a spreadsheet, staring at a blank word document or idly flipping through a report and your mind begins to wonder. Your attention begins to shift to the host of tasks that await you when you walk in your front door, to the date you had last weekend, to that vacation that is a few months away to _______ (insert the uncountable plethora of other distractions that can steal your focus and rob you of your productivity). How do we combat these moments of escapism in the workplace? We use our iPods, our music streams, the occasional YouTube cat video or a quick refresh of our social medias.

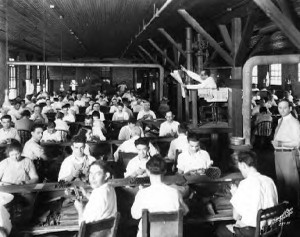

These quick mental breaks can often be just the refresher we need to pound out the rest of those numbers or get through the rest of that year-end earnings report. But, for the cigar laborers of the early 1900’s these technologically advanced mental distractions did not exist. The solution? The Lector.

The Lector or the el Lector was an individual who would show up in tandem with laborers of cigar factories, but instead of rolling, stuffing, gluing and packaging the Lector would instead read, and read and read and on the rare occasion, sing. Lector’s would read over the news of the day, novels of the time and of old and even recite famous poetry from the likes of Emily Dickens or Edgar Allen Poe.

The Lector or the el Lector was an individual who would show up in tandem with laborers of cigar factories, but instead of rolling, stuffing, gluing and packaging the Lector would instead read, and read and read and on the rare occasion, sing. Lector’s would read over the news of the day, novels of the time and of old and even recite famous poetry from the likes of Emily Dickens or Edgar Allen Poe.

Lectors were highly educated individuals who often spoke two, three or sometimes four different languages. From their raised platform (the tribuna as it was called) Lectors would entertain the factory workers with loud, booming voices, impressive displays of inflexion, character acting and yes, even the odd song. The grandfather of el Lector was Antonio Leal who first took to the tribuna in 1864 at the Vina Cigar factory of Behucal Cuba.

These lectors fostered a very curious relationship between knowledge and illiteracy of the common cigar worker during the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Most of the cigar rollers who worked in factories such as the Vina Cigar plant were largely uneducated. Growing up in impoverished Cuba, many of these men and women simply did not have the option to acquire the skills to properly read and write. Because of this, it was often difficult for many Cuban nationals to stay on top of the country’s political climate as well as news from the countries who sought so heavily after their nation’s chief export, the cigar.

Day in and day out, the cigar rollers of these factories would show up to work to be read to, sung to and have modern poetry recited to them. While perhaps unable to read, it was not uncommon for the average cigar worker to be well versed in classics of the time (Don Quixote, Les Miserables, The Count of Monte Cristo) or up to date on the power struggles going on overseas in England. What began to emerge was this curious duality of long, often ten hour days of manual labor that was then supplemented with an almost educational atmosphere.

The Lector, unlike the cigar laborers, was not directly paid by the cigar factory. Instead, the Lector was given a weekly pay-out from the employees of the cigar plant in exchange for their reading throughout their shifts. These Lectors began to shift into the closest thing that Cuba had to a movie star. As more and more Lectors began to extend their services to the different factories of Cuba, there would be the occasional standouts. The Lector who was known for reading in the best dramatic voice, the Lector who read the best news and the Lector who could stay on the tribuna the longest without a need of a break.

As time went on and political ideals shifted, news of other laborer unrest began to slowly be leaked into the daily readings by the Lectors. The factory workers of Cuba who had known nothing other than their long working hours and minimal pay began to hear news of factory revolts, laborer strikes for better working conditions and higher pay. Political ideals that were unlike that of Cuba began to be planted in the minds of the Cuban cigar laborer. Exposure to ideals like socialism and nihilism began to spread throughout the conscious of these workers and it wasn’t long before Cuba began to see protest and revolts of its own.

The owners of these cigar factories quickly put two and two together and 1931 would be marked as the year of the eventual extinction of the cigar Lector. The cigar moguls grew too fearful of what could become of their empire if the laborers who created it became too informed. While many did agree that the Lector brought higher levels of productivity to the working environment the implications of what could happen were too high and after debate for about a year the decreed of 1932 put an end to the institution of the Lector. Tribunas were torn down and replaced with radios, or in some cases, nothing at all. Soon after the eradication of the Lector, the cigar industry took a huge hit. Many of these laborers refused to work in the conditions of old and sought work in a variety of other industries.

Today, the Lector is largely an obsolete occupation but it is rumored that a few factories in Cuba still use them, continuing the tradition of providing a wealth of knowledge and the opportunity for modern day cigar rollers to be exposed to all walks of literature, news and poetry.

Luzzie Normand is a cigar enthusiast and freelance blogger. When she isn’t blogging, Luzzie enjoys writing her own serial comic books and slinging ink at tattoo shops.